Just-released figures expose … again … authorities’ grotesque distortions of “teenage suicide” in order to coddle popular attacks on social media

Look at the two figures below. See if you can spot some trends that might – just might – make post-2010 teenagers more depressed and anxious.

Figure 1. Suicide rates and average annual change per 100,000 population for teenagers and parent-aged adults (25-64), 1995-2023

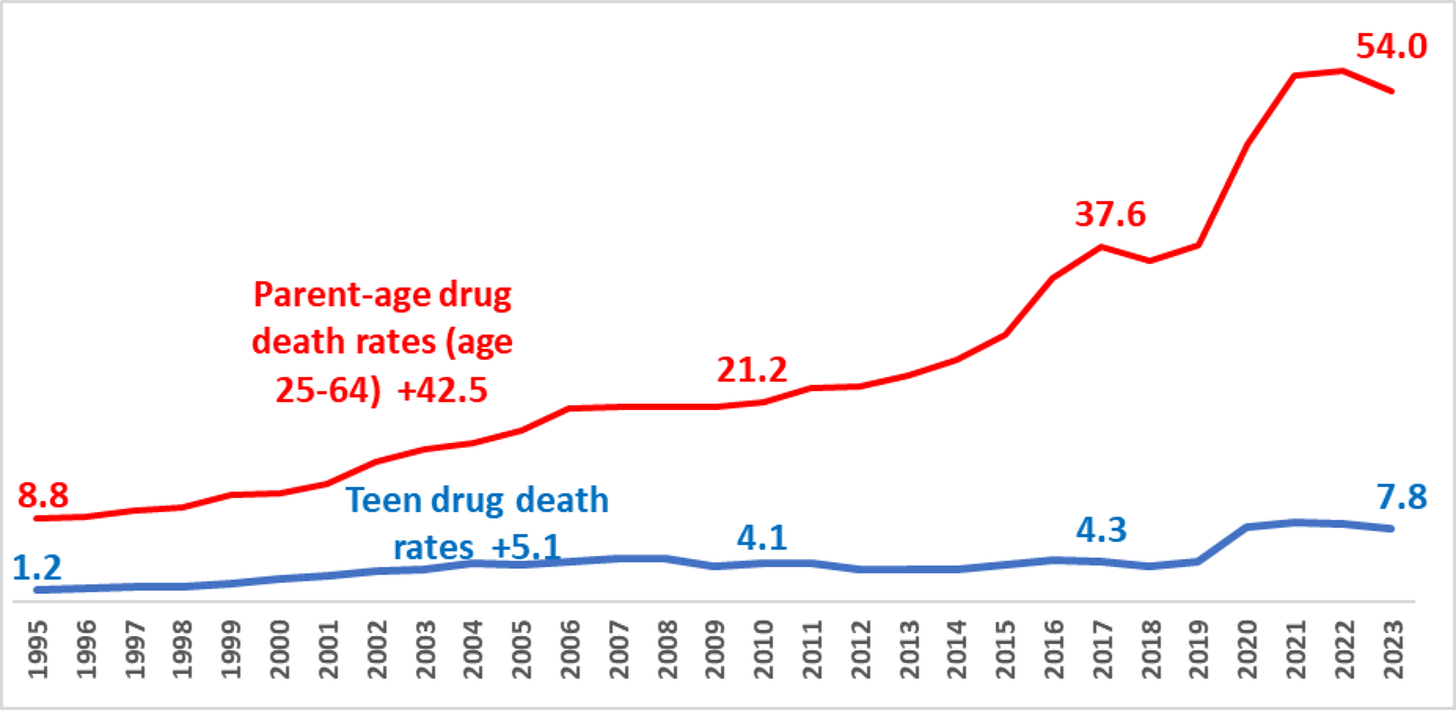

Figure 2. Illicit drug overdose death rates and average annual change per 100,000 population, 1995-2023

Source: Centers for Disease Control, 2025. Note: “Teen suicide rates” involve dividing all suicides by persons under age 20 by the population age 15-19. Average annual increases are derived from regression trendlines combining all years of data.

Amid the endless din over Generation Z’s mental health, no one mentions the Centers for Disease Control just-released final mortality figures for 2023.

Why not? Well, teen suicide rates fell again, as they have for the last six years. That doesn’t fit anyone’s needs. No interest, certainly not those blaming social media, profits monetarily, politically, or psychologically from publicizing real trends.

Parent-age suicide and overdose, not social media use, track teen suicide

Beginning in the late 1990s, suicide rates among parent-aged adults rocketed upwards while teenagers’ suicide rates fell substantially through around 2010. The trends directly challenge those who blame social media for teens’ problems.

· In 1995, just about no teens had access even to primitive social media or cellphones. Yet, they suffered elevated rates of unhappiness, loneliness, and, especially, suicide. That wasn’t supposed to happen, so it is ignored.

· In 2010, after online technology exploded, three-fourths of teens had social media and cell phones with online access. Yet, they had among the lowest rates of unhappiness, loneliness, and suicide ever recorded. That wasn’t supposed to happen, either, so it is also ignored.

Late-1990s and early-2000s teens were the last wave of Millennial teens. Their burgeoning social media use accompanied considerable drops in teens’ suicide and increases in illicit-drug overdose rates far lower than their parent generation’s. These teen trends accompanied stable trends in parent-age suicide and overdose during their 1990s childhoods.

Then, Gen Z’s first wave, born after 1997, started reaching teen years around 2010. They had experienced major increases in parent-generation’s suicide and overdose rates throughout their childhood, adolescent, and young-adult years. From 2010 to 2023, teen social media and cellphone use also rose marginally, from 75% to around 90%, along with teens’ unhappiness, loneliness, and suicide rates.

Now, suddenly, authorities started blaming more social media and cellphone use – which had accompanied falling teen suicide, unhappiness, and loneliness prior to 2010 – for teens’ rising suicide and unhappiness after 2010.

That doesn’t make sense, especially since bad post-2010 teen trends far more closely tracked parent-generation suicide and overdose rates that had been surging throughout their post-1997 childhoods and post-2010 adolescences.

The average annual increase in suicides and drug overdoses among parent-aged adults derived from standard regression trendlines (up 5.8 and 42.5 per 100,000 population, respectively) far exceeded those of teens (up 3.7 and 5.1). Rapidly increasing suicide and surging drug overdose are both iceberg-tips of larger, burgeoning mental health and addiction problems among parents and other adults around teens. Because suicide and overdose are very rare among pre-teen children, the effects of parent-age troubles did not show up until Gen Z reached teen years.

Why, then, do we hear that social media, not grownups’ crises, are driving teen suicide?

Because – unbelievably, given the post-2010 uproar over “teenage mental health” – no one ever asked teens about parent and family adult abuses and troubled behaviors… even though an avalanche of previous research showed powerful links.

Until, in 2021, the CDC’s biannual Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance finally ventured two tentative questions on domestic abuses. The results were so shocking the CDC’s 2022 press statement led off with “the disproportionate level of threats that some students experienced” contributing to their “poor mental health”:

· “More than half (55%) reported they experienced emotional abuse by a parent or other adult in the home, including swearing at, insulting, or putting down the student.

· “11% experienced physical abuse by a parent or other adult in the home, including hitting, beating, kicking, or physically hurting the student.”

· “More than a quarter (29%) reported a parent or other adult in their home lost a job.”

No one important cared. The “teen mental health” industry and commentariat unanimously ignored those key findings and renewed their insistence that social media use and peer cyberbullying were the only issues permissible to blame for teens’ poor mental health.

Even though analysis of the CDC survey associated parental abuses with teenage depression 13 times more, and infinitely more with teen suicide attempts, compared to near-nothing social media effects, psychologists Jonathan Haidt’s and Jean Twenge’s widely-quoted books, postings, and commentaries blamed social media and phones while never mentioning abuse at all.

Major media and politicians, sensational as always, preferred culture-war escapism to facing the increasingly grim realities millions of teens and children faced in their homes.

The 2023 bombshell

I congratulate designers of the CDC’s 2023 YRB survey for moving beyond this silence to include a half-dozen questions on teens’ household lives. These results were even more explosive – and even more ignored.

As I’ve detailed in past substacks, CDC analysts powerfully linked parent/adults’ abuses, mental health issues, drug/alcohol abuse, household violence, and jailings with two-thirds of teens’ depression and 89% of teens’ suicide attempts. Social media use and cyberbullying? Just about none, a second CDC analysis found.

Unfortunately, these debate-changing analyses were published in the CDC house journal, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, rarely read by the loud public commentators and politicians.

The CDC analyses, and mine, confirm the trends you see in Figures 1 and 2. The most likely known drivers – by far – of post-2010 mental health issues and related problems among teenagers are parents’ and household adults’ worsening, widespread mental health and drug abuse trends. The cold mortality numbers show that; teens’ responses to 2021 and 2023 CDC surveys show that.

But again, who important cares? Lambasting social media is so much more fun and self-satifsying than taking a hard, distressing look at what teenagers’ family lives are like. The next substack will examine some surprising teen attitude changes accompanying these trends over the last three decades.

Excellent work Mike, thank you.

Fascinating. I’m going to have to think about this for awhile. Thank you.