How Jean Twenge et al get the middle-aged drug abuse crisis and its effect on teenagers’ mental health disastrously wrong

Her latest apples-oranges comparisons of surveys and vital statistics, omissions of key data, flawed geographical comparisons, etc. severely understate the crisis

Once again, I appreciate psychologist Jean Twenge’s willingness to go where others in her field fear to tread – especially now that teens and social media have drawn misguided political attention.

Unfortunately, Twenge’s latest arguments are even less convincing than her previous ones, as will be detailed.

Consider first her denial: “It seems extremely unlikely that drug overdoses, drug abuse, or depression among parents is the primary cause of the rise in teen depression since 2010,” an assertion derived from a severely flawed analysis.

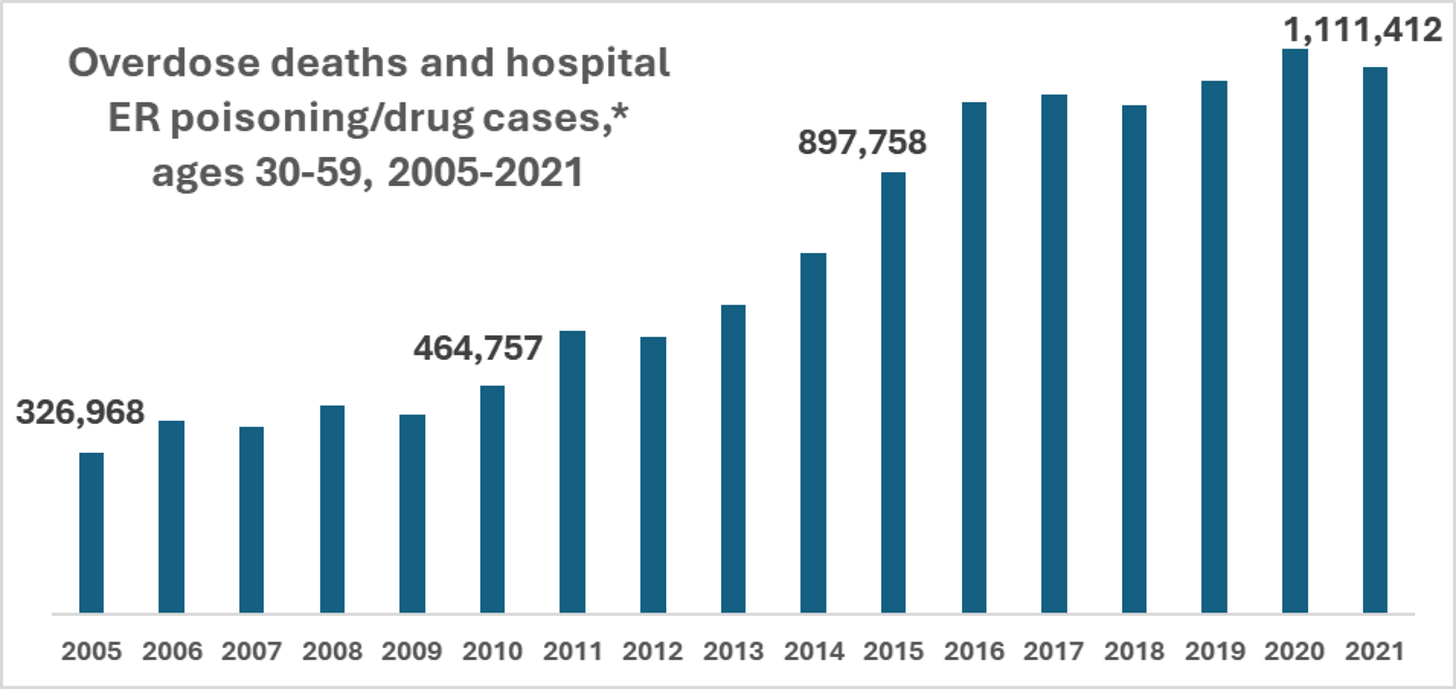

From 2010 through 2022, the period when teens experienced their biggest increase in poor mental health, some 800,000 grownups of ages (30 to 59) to be their parents, parents’ partners, uncles, aunts, other close relatives, teachers, coaches, etc. died from drug and alcohol overdoses; at least 12 million were treated in hospital emergency rooms for drug-related injuries, over 10 million were arrested for drunken or drug offenses, and 1 in 5 (some 20 million) were taking anti-depressants.

These are overlapping, not additive, numbers, and some involve adults who have no connections to teenagers. Even with these caveats, American youth face a staggering, skyrocketing crisis of middle-aged drug/alcohol problems in their homes and communities.

In 2022 alone, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimated over 5 million drug-related hospital emergencies in the 26-64 age group; the “rate of drug-related ED visits was higher among individuals 26 to 44 (3,265 per 100,000) and 45 to 64 (2,738 per 100,000).” These are large increases over 2011 and earlier.

Of the vital statistics indexes we can measure for ages 30-59, poisoning ER cases rocketed upward by 180%, from 671,000 in 2010 to 1.2 million in 2021, and annual overdose deaths soared from 29,000 to 76,000.

All in all, from 2010 through 2022, a staggering 13 million American 30-59-year-olds died from or were treated in hospital ER (estimated) for drug/alcohol overdose – equal to the entire middle-aged populations of Illinois, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. The annual midlife drug/alcohol death and injury toll nearly tripled over the period – again, during the same time teens were reporting more depression and anxiety.

Yet, Twenge contends that this massive, exploding drug abuse crisis among middle-aged parents and other grownups (including parents’ partners, close relatives, other household adults, teachers, coaches, etc.) couldn’t possibly be a major cause of mental health problems among teenagers. “Overall, the picture of middle-aged parents in this data is quite positive,” she insists.

No, it is not.

Sources: CDC 2024, 2024a. *A large and increasing majority of ER poisoning cases appear to be drug/alcohol-related, particularly opioids, but further refinement is needed.

Twenge’s analysis has other serious omissions. “It’s also difficult to reconcile how an increase in adult overdoses in the U.S. could explain why young people in Europe, Latin America, or Australia – places that have not seen such a sharp increase in adult drug overdoses -- are also more likely to be lonely, depressed, and engage in self-harm than they were 12 years ago.”

This is flatly incorrect. I’m not sure why Twenge, Haidt and colleagues continue to misstate easily-accessible data showing middle-aged drug deaths have soared across many countries: increasing from 988 in 2000 to 1,436 in 2010 and 2,637 in 2022 in the United Kingdom, and similarly in Canada and Australia, for example. Mistaken geographical comparisons will be addressed in another post.

Twenge agrees that “losing a parent increases the likelihood of depression” in children and youth, and that, “for every parent who dies from a drug overdose there are many more who abuse drugs.” She then goes on to deny this massive crisis, based on inapplicable comparisons of survey and vital statistics.

Twenge compares “the much smaller numbers of children who have lost parents compared to the large increase in depression.” That comparisons is as absurd as if I claimed, say, that some 8 million 10-14-year-old girls spend 3+ hours a day online, but just 190 committed suicide in 2022 – a negligible 0.000023 prevalence by proportion (even if being online caused all teen-girl suicides). So, why are Twenge and Haidt et al harping on such a trivial issue?

Twenge downplays real-world problems by citing surveys in which middle-agers SAY they’re just fine. “The use of illicit drugs other than marijuana has barely budged among 35- to 49-year-old parents. It has, however, increased significantly among those without children at home.” But non-parents also influence teens, and self-reported drug use has little to do with drug abuse, as the rapidly-rising drug death and hospital ER toll alongside widespread anti-depressant medicating of middle-aged Americans shows.

Twenge ends a flawed analysis with this non-sequitur: “There is no denying that drug overdoses have soared among American adults. This is its own crisis – we don’t need to tie it to the increase in teen depression to pay attention to it.”

That makes no sense. Whatever “we” choose to pay attention to, the fact is that teenagers don’t grow up in a rarified vacuum. Even understated estimates suggest that “one in five 12-17 year-olds live in households with parent who abused substances,” and millions more would be close to non-parent grownups in their households, larger families, schools, and communities to be affected by their troubles – easily enough to be capable of driving a 12-point increase in teenagers’ self-reported depression.

Wildly exaggerated social-media-blaming has ushered in a topsy-turvy discussion in which small numbers are treated as crucial, large numbers mean nothing, widespread real-life troubles by grownups are tossed aside or blamed on teens’ peers, and speculative cultural dangers are pushed to the forefront. No wonder the United States is such a uniquely high-risk society.

Excellent post! I think that Twenge et al have painted themselves into a corner by insisting that social media is the sole driver of the teen mental health crisis. At most, associations between social media and specific mental health variables are small, which implies that social media only has a small overall influence. I appreciate your calling attention to parental drug/alcohol use as a key contributor. I just finished a two-part series raising concerns about the way Haidt, Twenge, and others treat the data (https://statisfied.substack.com/p/social-media-and-the-mental-health). Details aside, I think your post illustrates that a strong case could be made for alternative explanations involving the parents of "the anxious generation."

Well-said as usual, Mike.