Critics of Gen Z and social media enjoy the luxury to pick and choose which times, conditions, and crises to face. Teenagers don’t

Blaming screens for teens’ depression ignores grownups’ and parents’ skyrocketing self-destruction afflicting millions of young people.

Jean Twenge’s May 22 posting asks: “Young people are telling us, with both their words and their actions, that they are suffering. Are we going to listen to them, or cover our ears and deny that there’s any problem?”

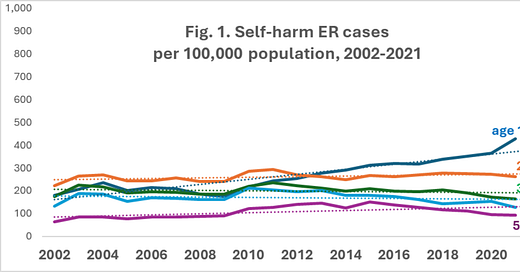

Yes! Let us stop denying. Let’s go straight to Twenge’s strongest point documenting the adolescent “mental health crisis:” teens’ increased hospital ER treatments for self-harm. There are not one, but two crises. I use the same vertical scale for both graphs to show their relative importance. I also include the entire 2002-2021 period available, since it encompasses Generation Z’s growing-up (what happens before adolescence is highly relevant to mental health).

Source: CDC WISQARS, Fatal and Nonfatal Injury Reports, 2024. CDC fatality figures show 96% of accidental/undetermined poisonings are from alcohol and drug overdoses; at least 55% of middle-aged drug overdose decedents are parents. Dotted lines incorporate all data into one linear trendline.

Note that ER admissions for self-harm (Figure 1) fall in frequency as age increases; that’s the opposite pattern than for completed suicides, which rise with age. Non-fatal self-harm may be one strategy distressed young women use to get help, which is why they rarely commit suicide. Still, we can agree this is bad: rising ER self-harm cases indicates rising distress among girls.

What could be driving their distress? Once again, Twenge and colleagues simply deny a much larger category of soaring, self-inflicted harm: drug and alcohol overdoses (Figure 2). Here, the pattern reverses. Teens have by far the lowest rate and smallest increase in ER cases, consistent with overdose death patterns.

Note that overdose/poisoning cases affecting ages 30-59 – the ones most likely to be teens’ parents, close relatives, teachers, coaches, etc. – rose especially fast from 2010 through 2021, the period teens’ depression, self-harm, and suicide also rose.

Hospital ER departments treated 670,000 self-harm and overdose cases involving 30-59-year-old patients in 2010, rising sharply to 1,205,000 in 2021. Another 800,000 30-59-year-olds died from suicides and overdoses during the period, rising from 51,000 in 2010 to 108,000 in 2021.

Altogether, 13.2 million American 30-59-year-old adults died from suicides or drug/alcohol overdoses or were treated in ER for self-harm or poisoning (overwhelmingly self-inflicted overdoses) during the 2010-2021 period. That’s equivalent to the entire middle-aged populations of Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Michigan going to ER or morgues for self-destructive tragedies in just 12 years.

Yet, I’m not aware of any survey that asks teenagers if parents’ and nearby grownups’ mentally troubled, suicidal, and drug/alcohol-abusing behaviors could be fostering teenagers’ depression and self-harm. That’s certainly a question we should be asking.

Twenge’s question beginning this post is a perfect one for Twenge, Haidt, and colleagues to confront, since they have relentlessly dodged mammoth issues affecting today’s young people. Are they going to continue to deny that the skyrocketing drug/alcohol crisis afflicting rising millions of grownups that teens interact directly with in their homes, extended families, schools, and communities could be why some teens understandably are more depressed and anxious?

One thing we do know: social media have nothing to do with teens’ suicide and self-harm trends, and very little to do with depression unless scientific rules are bent. That topic is next.

Well-said, as usual, Mike!