And now… a positive word about families

Do teens from healthy families have a social media problem?

Most of my posts variously analyze teenagers from abusive and troubled families, finding (not surprisingly) these teens are much more likely to be depressed, attempt suicide, and self-harm than teens from non-abusive families, and grownup abuses and troubles (not social media use) drive teens’ poor mental health. Further, social media seems to help most abused teens to cope with difficult conditions.

To clarify, the best information is that biological parents are less likely to be abusive and troubled compared to corresponding non-parents. The problem is broader, and unfortunately, that has made it easier for culture-war demagogues to evade.

For the first time, the Centers for Disease Control’s 2023 survey asks teens to detail “adverse” behaviors (emotional abuse, violent abuse, family violence, drug/alcohol problems, severe depression, jailing, and absence) of grownups around them – parents, stepparents, parents’ partners, guardians, and other household adults. Other than asking about sexual abuse by an adult 5 or more years older, the survey does not query abuses and troubles involving non-household “third party” adults like relatives, neighbors, teachers, coaches, health personnel, youth leaders, etc. who influence teens. So, the CDC survey underestimates problems adults inflict on teens that may prove depressing.

These limitations should be kept in mind for this post examining the one-third of younger teenagers (n = 1,700 of around 5,200 ages 13-15 the CDC surveyed) who report experiencing no household abuse problems – the generally healthy families social-mediaphobes pretend are typical. Does the fraction of teens under age 16 (the objects of social media bans) who have not been emotionally abused by parents/grownups nor suffered adult physical or sexual violence also report social-media problems?

Avoiding superficial “correlation equals causation”

The initial pattern might seem to weakly affirm social-mediaphobes’ insistence that heavy social media use is harmful. Of teens in non-abusive, non-violent homes, around 13% report frequently poor mental health, fewer than 3% (39 of 1,336 surveyed) report suicide attempts, and just 0.6% (8 of 1,323) report self-harm, all levels much lower than for other teens (or for adults). Still, frequent social media use accompanies somewhat poorer mental health:

Percent of non-abused teens under age 16 reporting frequently poor mental health:

· Never/almost never use social media: 13%

· Rarely use social media (less than daily): 9%

· Use social media daily: 13%

· Use social media many hours a day: 16%

The results once parental abuse is eliminated are uneven. Mathematical analysis of heavy social media use versus teens’ mental health yields a just-about-nothing effect size (d=0.15), typical of others’ findings. However, for superficial, single-factor analyses like Jean Twenge’s and Jonathan Haidt’s, a weak “correlation” is all that matters. Stop there! Don’t go any further! Any sort of finding would prove enough to spawn standard headlines (“Social media depresses teens even from good families!”) and win politicians and major lobbies.

If not abusive and violent adults, what else could be driving teens’ depression?

Here, we do go further. Even teens whose parents and household grownups are not emotionally abusive or violent still live with adults suffering from severe depression (13%), drug/alcohol problems (11%), absence (9%), and jailing (7%). Also, around one in 14 report cyberbullying; one in seven report being bullied at school, not feeling close to others at school, and/or suffering a concussion playing school sports; and one in five reports some degree of racism at school. Again, these are much lower problem levels than abused teens report.

For teens whose parents are not abusive, the association between their parents’ depression (in particular) and teens’ poor mental health is much higher (d=0.58), moderately significant) than for social media use. A teenager’s family does not have to be perfect, or even nearly so, but it greatly helps teens cope if adults are not abusive.

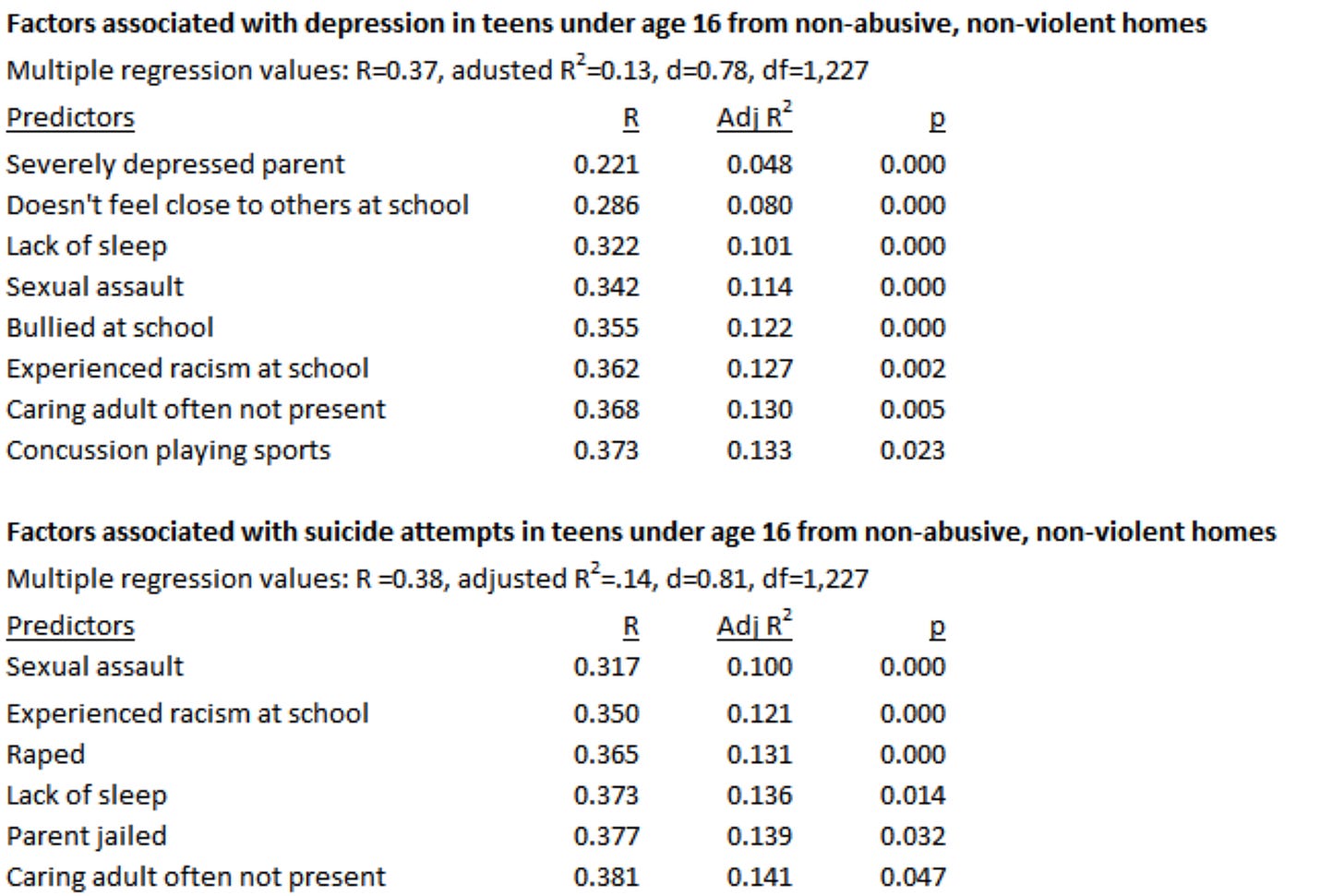

Normally, social scientists use such findings to pin down what factors other than abuse and household violence might be associated with teens’ depression. That is done by a mathematical technique called regression analysis, which in this case, ranks the factors in the CDC survey that might affect teenagers’ mental health (14 are evaluated here, including social media use, cyberbullying, sexual assault, rape, sexual assault by an older adult, lack of sleep, racism at school, not feeling close to others at school, school bullying, concussion from playing sports, severely depressed parent, drug/alcohol-abusing parent, jailed parent, and/or caring adult often not present):

Source of data: CDC 2024. Regression analysis is mine.

The cumulative R (raw correlation) and adjusted R2 (association) values shows the biggest negative factors associated with teen’s poor mental health are: having a severely depressed parent, how close they feel to others at school, how much sleep they get, whether they have been sexually assaulted, whether they’ve been bullied or subjected to racism at school, whether parents or caring adults are present, and whether they’ve suffered a concussion playing school sports. Together, those factors are strongly associated (d=0.78) with these teens’ poor mental health.

The same pattern shows up for suicide attempts, which are very rare among teens from non-abusive families. Still, there are predictors. Having been sexually assaulted, school racism, hours of sleep, and having a jailed or absent parent are by far the biggest factors associated with teens’ suicide attempts. The cumulative association is strong (d=0.81).

Social media and cyberbullying do not show up as even minimally significant among the 14 factors tested. In fact, the analysis excludes them decisively. As noted, those who have trouble with social media also have troubles elsewhere in their lives, and once these other factors are included in analyses, they dwarf any social media effects in importance.

So, teenagers from reasonably healthy, non-abusive families do suffer low levels of depression and very low suicidal inclination, but social media use is not the culprit. Among the many distortions in the anti-youth, anti-social-media crusade are the pretenses that all teens have healthy families and, therefore, social media use must account for the poor mental health some suffer. Both of these pretenses are false.

A further distortion is introduced by the failure to assess larger factors like teenagers’ concern for climate change and other global issues, which social-mediaphobes dismiss by simply assuming teens are shallow, cruel, and self-centered, flaws exacerbated by social media. This narrow view actually demonstrates the shallowness of social-mediaphobes, as will be examined next.

Another great essay:

https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/5027074-australias-social-media-ban-is-a-flawed-approach-to-protecting-children/

Honestly, if social media is so bad, then perhaps we should declare a state of emergency and "quarantine" all such platforms for all ages for "just two weeks" (right). And also have a smartphone buyback program like they do for guns. Then once the spell is broken, then We the People can decide collectively whether to go back to either.